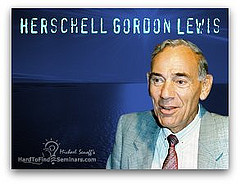

Michael: Hi, Herschell this is Michael Senoff. We’ve been emailing back and forth.

Herschell: Indeed and now we’re phone pals.

Michael: Herschell, like I said I do want to let you know that I’m recording this because it is my legal responsibility to let you know that.

Herschell: Well when the lawsuit comes up!!!

Michael: Right when the lawsuit comes! Did you have a chance to listen to any of those interviews I put up on the site?

Herschell: I took a look at some of the stuff from Jay Abraham and Gary Halbert and that bunch. I didn’t listen to any of the interviews because I feel that each one should be unique.

Michael: Each one is unique, and what I do is learn this stuff, and I have a lot of people who visit the website and want to learn from experts. I’m hardly an expert; I’m just a guy who asks a lot of questions. I benefit by learning from you and at the same time, I capture that on audio and offer it free to anyone who wants it.

Herschell: That’s very nice; you can be my Boswell, my Plato, whatever you choose to be.

Michael: Okay great. I don’t know that much about you. I’ll tell I do know that I’ve seen your advertisements in some of the direct mail newsletters and I have heard your name and I know you’ve written a lot of books on copy writing.

Herschell: One easy way to get some background if you like is to check my website. I have a very simple address, it’s HerschellGordonLewis.com, no punctuation and the only pitfall is the spelling of Herschell, which is Herschell. Sometimes I see it with only one “l” in it and it just won’t fly that way. As background I’ve written 26 books on various phases of marketing. The newest book was just published a couple of months ago. It’s called “Effective Email Marketing” published by Amacon Books, which is the publishing arm of the American Management Association.

Michael: Excellent; can I start from the beginning?

Michael: First in a nutshell, how have you come to where you are to have written this many book and mostly I assume are all specific on writing or copywriting.

Herschell: They’re all various facets of what one might call “forced communication.”

Michael: I want you to start from when you were a kid. Where were you born?

Herschell: I was born in Pittsburgh. My father died when I was very young.

Michael: How old were you?

Herschell: I was six. A few years later, my mother moved us to Chicago where I grew up and I went to school at Northwestern for years and years. We moved to Florida twenty-three yeas ago from Minneapolis because I had two goals in life. One was to one day own a piece of property with a palm tree on it, which you couldn’t do in Minneapolis. The other was to get away from that fur coat syndrome.

Michael: How old were you when you moved from Chicago?

Herschell: When I moved from Chicago to Minneapolis I was in my 40’s. My wife, Margot and I had a very good marketing account then in Minneapolis. It was called Calhoun’s Collectors’ Society and it was really a full-time proposition for us and we were really rocketing along with Calhoun’s. We both had a background working for the Bradford Exchange in Chicago.

Michael: You were in Chicago until you were about forty? Can I ask how old you are?

Herschell: I am seventy-three.

Michael: My dad is from Chicago and he’s about the same age. What high school did you go to?

Herschell: Bend High School, which I’m told now has fallen on evil times, but many neighborhoods have. That’s a long, long time ago. I can still envision the image of the building itself.

Michael: My dad grew up in Lincoln Park, or Lincoln Wood.

Herschell: There are two things; Lincoln Park is within the city of Chicago, Lincoln Wood is northwest.

Michael: I think it was Lincoln Wood.

Herschell: Lincoln Wood is where one of my publishers was until they sold to McGraw-Hill. That’s where National Textbook Company was. In this era of consolidation no companies tend to exist for very long. If you’d like I’ll complete the history with some of that too.

Michael: What were you doing all those years in Chicago?

Herschell: I had an advertising agency, which was called “Lewis, Nelson and Caan.” I was also in the motion picture business.

Michael: When did you start your ad agency?

Herschell: I started the ad agency in the middle 1950’s I believe.

Michael: How did you get into that? What led you to that?

Herschell: I was a school teacher. I taught English and the Humanities at Mississippi State. There is a point in many people’s career, especially when you’re young and full of hope and dream but you believe the only civilized job is in academia. To some extent that’s true and there is a definite benefit in teaching things such as English Literature or Victorian Era because Robert Browning is not about to write any new poetry so one set of lecture notes can last you a lifetime. That is the benefit of it. The detriment is that even though, teachers are not abused as you often will see in the press. You don’t work a lot of hours and the only nasty aspect is grading papers but if you have any kind of ambition of changing the course of human history it’s a dead end. I will cut through some of the saggy tissue that got me into that, but I wound up eventually in a radio station in Coatesville, PA where I was on the air from 6:00–9:00 in the morning and sold time the rest of the day. I hated it from the day I got there. I wound up immediately answering ads and, at the time then I was in the broadcasting business.

Michael: How old were you?

Herschell: Oh, I was in my late 20’s.

Michael: This was after you were teaching?

Herschell: This was immediately after I was teaching. I go out of teaching accidentally; well, I had been offered a job and I had to resign my position. You can’t just quit on the college level in the middle of a semester. By the time the semester had run out, the fellows who had offered me the job were out of business. Nasty blow, one of a number of mid-life crises, or that was well before mid-life!

Michael: Were you married then?

Herschell: I was married then.

Michael: Did you have kids?

Michael: So you were introduced to advertising because you were working for a radio station and you were selling advertising space.

Herschell: I was selling time all afternoon, yes.

Michael: Was that your first major sales job?

Herschell: When I was in school I was selling encyclopedias door to door. At that time, Sears and Roebuck had a thing they called The Americana Encyclopedia and I was out in the evenings selling encyclopedias. You talk about a brutal job. One thing I learned from that, which I have since decided to implement absolutely in telemarketing scripts that I write is, no adlibbing. Death and destruction, assuming that the original script was written by a professional, which Sears’ was and I learned with a lot of scar tissue that varying from that script always led to disaster.

Michael: How long did you sell encyclopedias?

Michael: How did you do? Were you good?

Herschell: I was not good; I wasn’t terrible. I sold encyclopedias, but I wasn’t on their top ten list.

Michael: I’m sure it was a pivotal experience in your life, the direct sales.

Herschell: In a sense because it is an introduction not only to the world of salesmanship but to the world of one-to-one salesmanship where resistance is a factor, whether that resistance is overt or passive. You learn a great deal and I know a lot of people in the direct marketing business for example who are not out there in the marketplace getting their hands dirty with the gutsy aspect of saying “Hey, these aren’t just numbers out there; these are people and we have to establish rapport with these people”. That’s one of my favorite words in marketing. Without that, and now that the Internet has become such a major factor, without rapport you’re wasting an awful lot of money.

Michael: What got you out of selling encyclopedias? What made you quit?

Herschell: Because I graduated. There was nothing nasty about it. I didn’t really like being out at night when I could be watching Captain Video or whatever some of these early TV shows were, but it gave me eating money. I was not affluent in those days. I was not a starving student; I was in the Army for a little while and the GI Bill paid for my graduate degree. I was also a graduate assistant at Northwestern, which helped. From Coatesville I got a job as assistant manager of a radio station in Racine, Wisconsin and I was at that station for two weeks and the manager quit and they made me manager, Suddenly, as though a switch were turned on I was an executive with invitations to be on committees and to expound on the glory and value of what I had to offer.

Michael: What kind of radio station was it?

Herschell: It was a daytime only radio station, WRAC and the problem with WRAC, as nice as it was, is that the other station in Racine, there were two, the newspapers owned WRJM, and they were a full time station, so we were always in second position.

Michael: What kind of format?

Herschell: It was a general format of news and music. At that time people began to say to me “Why aren’t you in television?” It’s like saying “Why aren’t you rich?” No one has that kind of control over his own destiny. So I began to answer ads and solicit attention from television stations. Lo and behold, I got a job largely through duplicity, I suppose as a producer/director of a station called WKY in Oklahoma City and this was a big powerful station owned by the Daily Oklahoman, which is the largest newspaper in the whole state of Oklahoma.

Michael: Were you married then?

Herschell: I was married then and I had one child who had been born in Racine. That was a job that was quite God-like; you press a button and pictures change in thousands of homes and that’s where I learned the basics really of motion picture production because the difference between live television and movies is simply a matter of the medium, not the technique. One day a fellow with whom I had gone to school, who owned a small advertising agency in Chicago, came flying down in a private plane and said “Quick, quick I need a television director for my agency. We are about to pick up the Household Finance account and they insist that I have a TV director.” He made me literally, like Mario Puzzo, an offer I couldn’t refuse. So I packed up heading back to Chicago; well as it turned out he did not get the Household Finance account. That was the next in the pre-midlife crises! During that period we were shooting some television spots and there was a little studio on Wabash Avenue in Chicago called Alexander and Associates and typical of this company there were two equal partners, a fellow named Mike Alexander and another man named Martin Schmidthuber and Marty Schmidthuber was so reticent that the company was called Alexander and Associates even after Mike Alexander left the company. Mike had been gone I guess about eight months when I started to do business there and I eventually bought his interest in the company so I had a half interest in this film studio but it was not enough to sustain life, and that is where I really gained the background that has helped me for the rest of my professional career, such as it is. Just to put Kraft dinner on the table, I got a job writing copy for the old Morlock Agency in Chicago.

Michael: They were an ad agency?

Herschell: They were an ad agency specializing in mail order, that’s all Morlock did was mail order.

Michael: Did you interview with them, or how did you get it?

Herschell: I interviewed with them; he had me write a sample piece of copy, which I thought was ridiculously easy, and that scared me because it was so easy, and he hired me on the spot. I began writing copy for Morlock and that went on for years.

Michael: How old were you when you started?

Herschell: I would guess thirty.

Michael: How many years were you writing copy there?

Herschell: Forever! Long after the film business took hold, long after I had my own ad agency, I was still writing copy for Morlock.

Michael: Did you have a mentor?

Herschell: The only mentor I would have had would have been Morlock himself.

Herschell: He was pragmatic. He also called me “Son” which I appreciated. In fact I’m guessing the relationship ran for close to twenty years.

Michael: He was kind of like a father figure?

Herschell: He had two sons-in-law in the business with him. One of the sons- in-law was a fellow named Lawrence G. Barton, they called him Buzz Barton. Buzz eventually went off and founded his own agency, which he called B B and A, I think they’re still in business.

Michael: I’ve heard of B, B and A.

Herschell: I began to write copy for him because we had that kind of relationship before, so it went on into the next generation.

Michael: Morlock was specifically for direct mail?

Herschell: He was strictly mail order. So old was the agency, he had a lot of classified ad business; on Wednesday afternoons we all sat there paying for these ads by stamps. That’s how antiquated the technique was, but Morlock had a couple of philosophical inclusions which really appealed to me. One, cheat nobody and two, pay your bills. I wish that everybody in that business had such a philosophy.

Michael: Did he have a pretty big agency?

Herschell: No, no, I was the only copy writer; he had old women in there; he had old typewriters, some of them I thought he’d gotten out of the vault of the Smithsonian Institution, but that wasn’t the point of it at the time, nor did I care. Morlock paid me and he paid his people and he paid his suppliers and he paid for his media bills and he paid for printing; it was an ethical operation even though rather hopelessly old fashioned.

Michael: Were you testing the results of your copy?

Michael: So it was a science, you were testing headlines?

Herschell: Always, I maintained that particular aspect forever.

Michael: Where did you learn about all that?

Herschell: I learned it by having a couple of occasions that we didn’t test then we began to wonder “Might it have pulled better if we did something?” So we did something else and it pulled better. In fact, back at the Bradford Exchange when my introduction to that company which was very peculiar on its own, they were running little four inch ads and they were paying $11 for an inquiry, not a sale, an inquiry. They wanted to get that down to $3. You might regard that as an impossible dream. The Bradford Exchange at that time was owned by a fellow named Rod McArthur who was the son of John McArthur who had founded Bankers’ Life Insurance, owned Palm Beach and the other half of Park Avenue in New York and Rod was something of the prodigal son. He had a defunct company called Bradford Gallery, which he re-titled Bradford Galleries Exchange to sell collectors’ plates. I had no notion what these were, and at the time I had founded an agency in the Wrigley Building in Chicago and our biggest client went bust. You see at the time I didn’t want mail order. I felt that Morlock’s was too piddling. I wanted television advertising; after all I owned film equipment! I wanted four color pages in Time Magazine because that’s where the fifteen percent billings were. Well sure enough my biggest account, which was a heavy television advertiser, went bust owing me ninety days worth of billing and suddenly I did not have a half a floor in the Wrigley Building. I had a little office in Highland Park and I didn’t have a bunch of people around, I was no longer an executive, I was back on the keyboard, I had four people including me and here I am moaning about “How can this happen to a nice guy like me?” There was an agency then, and it was the only direct mail agency I knew. It was called Marshall John. Those were the first names of the two fellows who owned it and I don’t remember their last names any longer but somebody from Marshall John called me and said “We have a client we can’t satisfy. Do you want to take a shot at the piece of copy?” I asked what that was, then I asked my standard question “Will I get paid?” He said “You’ll get paid on delivery.” The client it turned out was the Bradford Exchange.

Michael: For anyone listening, what was the Bradford Exchange at that time? What were they doing?

Herschell: The Bradford Exchange at that time was trying to make a New York stock exchange out of collectors’ plates. You may think that’s an insane idea, and maybe in the 21st Century it is because Bradford has dropped that notion. But it wasn’t then, and people were buying the plates and following the monthly listings of the supposed value of these plates. It was a maniacal scheme conceived by Rod McArthur, who was a mad genius in his own way. Well, I wrote this copy for the Bradford Exchange and it was pure fantasy because produced collectibles are an oxymoron to start with. Again it was ridiculously easy because fact didn’t enter into it. It was strictly fantasy masquerading as fact, so I delivered that copy and they paid me as I delivered and I said “How long has this been going on? I don’t owe CBS eighty-five percent of this.” So Bradford became a regular client of mine and then they asked me to come into their office one day a week. They were in a town called Northbrook and I had this little office in Highland Park and it made great sense to me, so I was in their office one day a week, then it was two days a week, and then they asked me to put together a creative staff for them, which I did.

Michael: Were they selling lots of plates?

Herschell: They were selling lots of plates.

Michael: How were they advertising, what mediums?

Herschell: They were running ads in FSI’s; we had a tremendous direct mail program going. We were sending out direct mail at such a clip, I think the only people who were mailing out more than we were was the Billy Graham group.

Michael: How many pieces were going out each month?

Herschell: They were going out by the millions early on. Bradford had achieved a house list of people who were salivating over the next plate.

Michael: How big was the list?

Herschell: I don’t remember really; it was in the several hundred thousands even then I think. It wasn’t segmented the way they do it today. That was before we really had computer help because computers came into the mixture towards the latter part of the 1970’s and that’s just when I left the relationship with Bradford because I had a thing with Calhoun. Calhoun’s was the best cold list for Bradford. Here was an outside company whose list was pulling almost as well as the house list.

Michael: Describe what Calhoun’s was.

Herschell: Calhoun’s was an organization in Minneapolis that sold strange things such as gold foil stamps supposedly issued by an island off the coast of Scotland as an official issue. It was insane but it was working but they had not plates. So here I am the king of plate sales so I made a deal with Calhoun’s to prepare a plate series for them. They’d never been in the plate business. I went up to meet with them, that again was a strange story, but the fellow who ran Calhoun’s was a man named Stafford Calvin. I went up to meet with him and he said “Here’s my idea” and he showed me what he wanted to do, which was a Christmas plate with a painting by a paraplegic woman who held a brush in her teeth. I said “Mr. Calvin people will buy a Christmas card out of pity but they will not buy something to display. The quality of the art is not worthy of that where people will have to explain that the woman is a paraplegic.” Of course by this time I was kicking myself for going up there! He said “Well what would you do?” I said “I would have a continuity program.” He said “Can you come back in a week with an idea?” I said “Sure.” He was paying the airfare. A week later I went back there and I figured “In for a penny, in for a pound”. Instead of an idea, I had the entire program written out for a twelve-plate series called “The Creation,” the twelve plates from the Book of Genesis by the noted artist “Name” because there was no artist, there was no deal. So I showed him this and it was in copy form only and he said “How are we going to sell this?” and I told him “The difference between this and a Bradford promotion is that we are going to give people matched registration numbers.” One thing that had become clear to me at Bradford was people don’t care what’s on the face of the plate; they care about what’s on the back of the plate.

Michael: They’re buying on the speculation of the value going up.

Herschell: Exactly, so the back stamp became crucial here. We were going to give them matched numbers and the threat would be, by telemarketing or whatever else, if they didn’t continue with the twelve plates that they would lose their numbers. He said “Can you have lunch with me and my partners?” And I smelled blood. It turned out they wanted to go ahead with it and they authorized me to do the entire twelve plates, including finding an artist, having the detail decals made which we were going to do in Florence, Italy, having somebody else fire these plates, we found a company in Newcastle, Pennsylvania; the whole thing was in my hands to do. The Creation was, to put it very conservatively, a smash. We killed them with the Creation.

Michael: When you say the Creation the actual production of the designs or the rollout with it?

Herschell: The details; they went through the roof; well they should for a company like that. Bradford never had its own plate series.

Michael: What was the offer on the rollout?

Herschell: The offer was that the plates would sell for $19.95 or $29.95 each, you would own your registration number, and each plate would come with its certificate of authenticity and all the other stuff that came with it. When we first started mailing it we only had two pieces of art we were eager to get in the mail. The artist was working furiously to give us more, so the early mailings only showed a couple of plates and then we flushed it out with other paintings the artist had done. Looking back at this it was a lot of guts to do that but it did work.

Michael: When people signed up they signed up for a monthly plate for the year?

Herschell: Exactly, and those who charged it to a credit card got it automatically. Those who paid by check, it usually worked. At Bradford as I recall the average for a twelve-plate series was four, people would collect four. Some people collect the first one because they always called it a first edition; those are magical words, the word “charger” in subscriptions, meaningless but it does have an emotional impact. The average at Bradford was four; the average at Calhoun’s was nine. It was much more profound.

Michael: And it was all going to Calhoun’s “a good thing” list?

Herschell: No, no we were buying outside lists too. But the Calhoun’s list of course, there was never a problem.

Michael: You look in the National Enquirer and you still see all these collectors’ plates.

Herschell: Sure you do. You see them in inserts.

Michael: Basically this is the origination of this business.

Herschell: That’s where the whole thing started. Actually the first collectors’ plate was made in Denmark in 1895. I’m sure when Bradford came along all we had was a Blue Christmas plate, so Bradford did transform the whole notion of collectors’ plates. Here was something else that happened. With the eleventh and twelfth plates of the series we enclosed a little piece of paper offering them a second series called “The Promised Land,” twelve plates from the Book of Exodus. That was the only advertising for that and from that little piece of paper. We had a forty-three percent buy-through. Those golden days are gone, I’m sure. Then my wife Margot who had been working at Bradford, the two of us began to really rock and roll and we had a series called “The Golden Age of Cinema.” We got MGM to allow us to do that for a royalty of course. We had other plate series for Calhoun’s. At one point during some particularly bitter cold days we looked at each other and said “This is our last winter here” and we reached a very quick agreement. At that time, we did have FedEx but we didn’t have fax machines so we were only meeting with the people at Calhoun’s maybe once or twice a month. The two of us went to Stafford and said, “We’re taking the place in Florida.” He quickly said, “Your deal’s cancelled.” I said “Hold it a second. We’ll maintain an apartment here and whenever you need us we’re here. We’re only meeting a couple of times a month anyway and we can send your stuff by FedEx.” He said “Your deal’s cancelled.” Margot to her eternal credit said “All right, you will pump gasoline, I will wait on tables, and we’ll do whatever we want.” With Calhoun’s purse ringing in our ears, off we went to sunny Florida.

Michael: Where in Florida?

Herschell: Fort Lauderdale. Originally to a town called Plantation, which is a suburb of Fort Lauderdale.

Michael: Why there? Did you have family there?

Herschell: No we didn’t have family there but one of the companies who dealt with Calhoun, which was a company called Viking Import House was in Fort Lauderdale and we had come down to Fort Lauderdale on business and the fellow who was the sales manager at Viking lived in a town called Plantation. I had shot features in Miami but I had never really explored Fort Lauderdale as a location. We liked Plantation, it was a bedroom type community and we didn’t have any particular spot to go to and Margot had grown up in the San Diego area. We felt that since a lot of our business might be coming and a lot of travel might be European we were better off on the East Coast. Really it was just a wild decision that we never have regretted.

Michael: How old were you then when you moved to Florida?

Herschell: I’m guessing sixty, close to that. Some of Calhoun’s competitors found that we were at large and the phone started to ring and we did “The Greatest Show on Earth” for the Hamilton collection. We did the “American Rose” plate for the International Museum out of McAllen, Texas.

Michael: So you were designing and creating plate campaigns.

Herschell: We were designing and creating plate campaigns.

Michael: Did a direct mail and advertising go with the campaign?

Herschell: Absolutely. Margot would handle the art and the positioning; she became an expert on putting art onto porcelain because with the ceramic pigments the colors change when you fire the plates. Many times we would see a plate that started out to be blue and turned out to be green. She was the expert in that and well recognized within the world of plates for that. So Margot would put the art together and I would sell it.

Michael: Okay, so you’ve had twenty years experience in selling plates.

Herschell: I’ve actually sold more plates that anybody.

Michael: Why do people buy plates?

Herschell: People buy plates because it gives the sense of possession. Many people who could never afford an original piece of art found they could have what they called fine art in their homes, and often that’s how we sold it. Exclusivity was the factor. With Bradford it was a different story, it was exclusivity matched up with the possibility of value increase, which sometimes was fictional but that was the way it was sold.

Michael: Did each plate have a different number on the back?

Michael: So they were all individually numbered.

Herschell: They were all individually not only numbered, but hand numbered.

Herschell: I know that sounds funny but that’s a sales word too.

Herschell: I have to tell you the next major change. I had been writing or doing projects for a company out of McAllen, Texas, which was called The International Museum. The fellow who owned that, who ran it was man named Frank Schultz and Frank and Marilyn Schultz were old timers in the direct mail and mail order business.

Michael: You were in Florida?

Herschell: I was down in Florida, I still am in Florida. One fateful happy day Frank Schultz said to me “Hey do you ever write anything except plates?” I said “Of course I do.” He said “Well I have another company and we’ve had the same control mailing for about nine years and it’s getting tired. Do you want to take a shot at it?” Sure.

Michael: What was this guy doing?

Herschell: Frank’s other company was called Royal Ruby Red Grapefruits. Frank was on the board of the DMA at that time. He was one of the sweetest people ever in this business. So I wrote a package for Royal Ruby Red Grapefruits and I beat his control. About three months later I got a phone call “Mr. Lewis my name is Fred Simon. I’m the President of a company called Omaha Steaks. Frank Schultz told me about the package you wrote for him. Do you want to write one for us?” Sure! I think Fred is the fourth generation in Omaha Steaks. They were founded in 1917. I’m still dealing with them.

Michael: So he was the president? Herschell; He was the president at the time; he may still be the president or the chairman, and as I say, you talk about nice people. Some of the people in this business are not so nice, but people like Frank Schultz and Fred Simon are gems.

Michael: Usually the more successful people are it seems like the nicer they are.

Herschell: I’d like to think that because I regard myself as successful. So I wrote a package for Fred Simon and it did very well for him and he told everybody, and at that point, the dam broke. On top of which I was beginning to write articles for the old magazine called Direct Marketing.

Michael: Was it the original?

Herschell: It was the original.

Michael: When did that start?

Herschell: In the 1930’s. I stayed with that packaging in fact for 200 consecutive issues.

Michael: You wrote an article for each issue?

Herschell: Every issue was called “Creative Strategies.” The only reason I quit writing for them even after I had begun to write for other magazines it turned out that someone else, whose name I will not give you, began to rewrite my old articles from nine or ten years before and they were appearing in the magazine. There were two columns called “Creative Strategies,” one was mine and one belonged to this other fellow.

Michael: Was his in the form of an ad?

Herschell: No, no, it was a column and I called the editor at that time of Direct Marketing who obviously hadn’t even been there when I first wrote these articles, and I said, “Are you at all aware of what this is?” He said, “Oh is that right?” The next month there was another one! I had written about 195 articles and I figured, like some baseball player in a consecutive game, I'd go to 200 and quit. By that time I was already entrenched with what I felt was a more contemporary magazine called Direct. For Direct I was and am their curmudgeon at large, I’m on the inside back cover and I love the magazine and I love the people who run it. Ray Schultz, the Editor knows how to edit a magazine. I’m also the copy columnist for Catalog Age; I write a monthly article for selling newsletters called Better Letters and for two magazines in the UK. For catalog and e-business, I write a column on catalog copy and for one called Direct Marketing International I write a column called “Copy Class”

Michael: You’re doing a lot of writing!

Herschell: I’m doing a lot of writing.

Michael: How much writing are you doing a week?

Herschell: I’m at the keyboard most of the time.

Michael: When that guy was knocking off your articles, you own the copyright on all of those articles, right?

Herschell: Denny Hatch told me that; I’d made no attempt at that time.

Michael: You didn’t realize at that time that you owned the rights to all that?

Herschell: That didn’t bother me that I owned it or didn’t own it. What bothered me was that the magazine didn’t care. Anybody who wants to reprint one of my articles, God bless them. I don’t like the idea of someone simply swiping the notion and usurping it under his or her own name.

Michael: Were they copying them outright?

Herschell: A word was changed here or there but if there are ten rules for letter writing and there are the same rules, the conclusion has to be obvious.

Michael: Because they didn’t do anything about it you said “Forget it, I’m not writing for you any more.”

Herschell: That’s exactly right.

Michael: You never went after the guy who was knocking them off.

Herschell: No, what am I gong to do? That’s like saying, “I spilled some coffee on myself, and it’s your fault.” I just couldn’t take that militant point of view; I was irritated, yes but anybody who was that poverty stricken and had come to that intellectual curiosity is more to be pitied than censored. Some of the stuff was not only obsolete but it was by that time so well known that I felt that any editorial judgment would have killed it to start with. Here I sit and I’m looking out at the ocean from the 26th floor of what is regarded as one of the premium buildings in Fort Lauderdale and I thank my stars that I got into direct marketing in the first place. I had a company called Communicomp and Communicomp was originally my wife Margot and I, and Communicomp celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1997 or 1998 but by that time the spirit of change was in the air and I’ll tell you what it was. We had moved the company to Florida; of course now with email and fax machines, which are almost obsolete, I do business primarily by email and I deal with clients all over the world. I have a client in Japan, I have two clients in the UK, I have clients in Germany, and it’s instantaneous. I love it, I love being alive while this is going on. One day I had a phone call and a man said to me “Mr. Lewis my name is Charles Peebler and I am the President of Bozell, Jacobs, Kenyon & Eckhardt and I think we should get together.”

Herschell: Fortunately, I didn’t say that! I said “Well come on down”. By that time, our daughter Carol had joined us. She had been running an ad agency in Chicago, a direct marketing agency and she was sick of the climate there and said, “I want to come down to Florida and join you.” I said “By all means.” Carol is immensely talented on a creative level.

Michael: You have one daughter?

Herschell: We have four daughters and a son. Carol came down and changed the complexion somewhat. She wanted to open an office, that was her background and instead of the two of us working out of our house, which we continue to do, Carol had an office with a receptionist and account people and people running around and a whole art department with a bunch of people on Macintosh and I said “Holy mackerel!”. She was doing business with Carnival Cruise and First Union Bank and it was going very nicely. I told Chuck Peebler to come down that weekend because I figured “Okay on a weekend he can’t see how few people we have.” He came down and he invited Carol, Margot and me to come up to New York and meet the people at Bozell and within very short order Communicomp became owned by Bozell, Jacobs, Kenyon & Eckhardt. I became Chairman rather than President of Communicomp and I was also Chairman of a strange, unreal organization called BJK&E Direct.

Michael: Was that part of that company?

Herschell: It was supposed to be an umbrella over the overall direct operations of Bozell. It didn’t really work out that way because they had a “get off my turf” attitude in some of their offices.

Michael: Communicomp was you your wife and your daughter?

Herschell: We were the three principles. By that time, we had employees, but we were the three principles and each of us got a three-year employment contract with Bozell. As we approached the first anniversary of our relationship with Bozell another company called True North, which was Whitcomb and Belding bought Bozell. We didn’t know whom we were working for because there was a whole new set of faces. Chuck Peebler came down once again and he said to me “I’ve got a deal for you and Margot if you want it.” I said, “What’s the deal?” He said, “Well True North is giving us restructuring money and if you’d like I can buy out the last two years of your contract and Margot’s. The benefit to you is you get the money now. The benefit to Carol is she can hire five or six people and staff up that operation the way is should be.” I considered this for about four or five seconds!

Michael: Can I ask what kind of money they offered to buy you out?

Herschell: I am not at liberty to disclose. I wish I could but I can’t tell you.

Michael: But it was good money and it didn’t take you too long to think about it!

Herschell: That’s a wonderful interpretation. To my total delight when the papers came through they released me from the 2-year non- compete that had been built into the original contract.

Herschell: Some of the old clients like Barnes and Noble and Omaha Steaks and some of those companies came back. We almost in a defensive posture formed a DBA called Lewis Enterprises, which is the name I’m doing business under now. About eight months or a year after that a bigger agency yet called Interpublic bought True North. You talk about a fish swallowing a fish swallowing a fish!

Michael: Is this still happening today?

Herschell: Oh yes, consolidation is fierce. Interpublic very quickly closed Communicomp altogether. They felt it was a flea in the air; I felt it was profitable. It was profitable but profit is a matter of percentage and in terms of total contribution to the Interpublic Empire, it was nickels and dimes. I guess they didn’t want to bother with it so I was glad to be out of it.

Michael: So Communicomp as an agency, you were making your money as an ad agency percentage at that time?

Herschell: No, we were always direct as Commnicomp; we were not placing space ads. We would turn that over to somebody else. Usually if somebody wanted to run space we would create the ads and turn them over to Franklin and Joseph, which I think is now called Roger Franklin Advertising.

Michael: What kind of deals did you set up with a client of Communicomp if you had a direct mail client?

Herschell: We had all kinds of deals. One would be on a monthly retainer basis in which whatever they wanted to do we would do over the period of a month, and every six months we would reevaluate the thing on whether somebody got hurt or not. The other was on a per-job basis. To this day, I have a rate schedule, so if I’m not here somebody else can quote what letter costs, what a brochure costs, what catalog copy costs, what email costs, what web design costs, it makes it a little more comfortable in standardizing prices.

Michael: Nothing on percentage of gross sales?

Herschell: There are two reasons; first of all I don’t want to be somebody’s policeman and the other is I don’t want to be somebody’s partner. I know people who have done that and they have wound up always in antagonism. There’s an old saying “There are two times when partners fight; when they are making money and when they are losing money.” I have many, many times – probably hundreds – been asked, “Do you want to make a deal whereby we share?” My answer is “No I don’t because first of all if I’m going to write a piece of copy on that basis, I don’t want any editing.” Many clients resist that because their own ego is on the line, and they may have a better idea for all I know, but I don’t like that, that’s not the way it can work. How do I know what the numbers are? I’m not going to send an accountant in there.

Michael: You don’t want to screw with it. Herschell; I don’t want to screw with it. I never had any need to.

Michael: Talk about ego; over your career how many times have you seen ego destroy a campaign?

Herschell: As a guess 20,000! I remember way back when I had my little agency, I had an account that was selling air conditioners. This fellow wanted his golf pro to do a TV show so he could show off for his golf pro! And it was a total disaster, the man was a mumble- mouth to start with and it just didn’t work. If you don’t want to do it, we’ll get somebody else.

Michael: The best way to sell an advertisement is to show them his own name.

Herschell: We’ve seen that many times. Lee Iacocca had a certain posture in that respect. Many times now we’ll see other people who come up there, car dealers or real estate people or investment people who want their names up there, who want their friends to say “Hey I saw you on television”; pure nonsense.

Michael: We call that image advertising.

Herschell: To me image advertising is a way to avoid having to count the results.

Michael: Is that because the agencies don’t want to be accountable for the results?

Herschell: The agencies are terrified. Or else they feel, if somebody said, “I know what we’ll do; we’ll put him in the spots, we’ll put Dave Thomas in the Wendy’s spots, and that way if the spots work we’re heroes and if they don’t, he’s the bum.” Meanwhile, all his friends will say, “Hey I saw you on television.” That thing started off poorly and in the middle, it was all right but eventually before he died, it became something of a joke.

Michael: You come from a direct mail background for all those years doing plates where you’re accountable for your efforts and it’s either sink or swim. You watch TV today and you look at these image based advertisements, what’s your thought when you’re sitting there watching TV seeing this stuff?

Herschell: My thought is that many people are wasting many millions of dollars. These companies are so obscure one can’t tell what they’re all about.

Michael: Is it getting worse?

Herschell: It’s much worse and I’ll tell you why. The TV stations in their consummate greed are splicing two commercials together, often for two differing and competing makes of automobiles without even a dark frame in between. The result has to be great confusion on the part of the consumer. Another aspect is this apparently insane desire not to tell you what it is they’re selling. That’s the purpose of marketing in my opinion and I’m not about to change it at this late date. It’s to cause the viewer, the listener, the reader to perform a positive act as the direct result of having been exposed to that message, how many televisions spots don’t do that? Now we have email, which in my opinion is the future. Email to me, and I’ve often said this, I say it in speeches, I’ve said it in books, to me email is the most important evolution in communications since the Guttenberg Bible. What do we have in email? We have duplicity right and left, and in my September 15th column in Direct there are companies such as Continental Airlines and Sprint who try to obfuscate rather than to communicate, where there is no question the web is price driven. It positively is, but that doesn’t mean you can’t tell people what you’re giving them for their money, or tell them that what’s free, is free if, or when. Those two key words if and when have some posture.

Michael: If you absolutely studied and understood how to write just one concept, if you could learn and master how to write a good benefit- oriented headline you could blow the competition away. There is so much poor advertisement and letter writing skills it would be an unfair advantage even if you had the mildest education on how to write a headline.

Herschell: I agree with you absolutely.

Michael: There is a lot of opportunity. A lot of people listening to this are new to marketing, are new to learning and understanding how to write copy and what advertising is all about.

Herschell: To those people I would say “Please, please don’t destroy the medium by assuming that everybody out there is a P.T. Barnum sucker.”

Michael: What do you think is the most important aspect in writing a communication?

Herschell: I would call it the clarity commandment, it’s too important to be called a rule. The clarity commandment is this; when you choose words and phrases for force communication, that’s the business we’re in, clarity is paramount. Don’t let any other facet of the communications mix interfere with it.

Michael: What about the headline; what is your view on how important a headline is?

Herschell: Well the headline determines of course whether somebody is going to read through it or not and that becomes even more important email where the subject lines, some of them are so impossibly stupid you wonder if a half-wit oyster wrote those but the headline has to be provocative without being duplicitous.

Michael: Who are some of your favorite educators? I’m sure with all the writing you’ve done you do a lot of research on your own. Who were some of the mentors you’ve learned from? If you could encourage somebody to study the great masters of copy writing, who would it be?

Herschell: There’s only one and that’s Claude Hopkins.

Michael: What do you know about Claude Hopkins?

Herschell: He was the first star in copy writing under a man named Albert Lasker, who founded the agency, which later became Whitcomb and Belding. Lasker gave this man free rein. The other was John Caples, who wrote the classic ad “Do You Make These Mistakes in English?” No, that was Sherwin Cody. The Sherwin Cody ad ran unchanged for 45 years. Can you imagine an ad running 45 insertions today? It’s impossible. John Caples wrote “They Laughed When I Sat Down To Play The Piano.” The whole idea was to be provocative so a state of mind was created as people read into the ad. I’ve tried to adapt that to contemporary communications.

Michael: Who was Sherwin Cody?

Herschell: Sherwin Cody was an ancient character even when I was a kid. I have no idea of where he was born or how long he lived or any of that. He was running these ads in boys and men’s magazines and in most of the consumer publications, and that was a standard ad for 45 years “Do You Make These Mistakes In English?”

Michael: How about Clyde Bedell?

Herschell: I’m not that familiar with Clyde Bedell except for the name.

Michael: When I first contacted you, I was searching for great advertising books and I went onto Amazon and saw your book “World’s Greatest Direct Mail Sales Letters.” By the way, I sent you a check for that. I couldn’t find the book anywhere.

Herschell: That’s strange.

Michael: It’s out of print.

Herschell: Well that’s horrifying to hear because what happened was that the publisher of that book which is MTC National Textbook Company was bought by McGraw Hill and since that time I’ve had no communication at all from anybody there except the semi-annual royalty payments so I didn’t know if it was in or out of print.

Michael: Talk about that book; how did that project originate? Who approached you on it?

Herschell: What happened was that Richard Hagel who was my editor at MTC and later founded his own imprint called Racom Books, and they are the publishers of one of my books called “Marketing Mayhem” he told me that an old friend of mine named Dick Hodgson had a book about great sales letters. In fact, two of my letters were in Dick’s book. Dick was pretty much retiring and was not about to update that book and some of the stuff was pretty old and I did not want to cross paths with him because we go way back so I contacted Dick and said “Would this bother you?” He said, “No I don’t care.” Carol Nelson and I wrote 500 letters to everybody we had ever heard of in direct marketing, to agencies, to individuals, to by-line names in magazines asking for submissions for this book. We asked for, and, as I am much familiar with awards, verification that this stuff was effective. Everybody lies, and much of the judging was quite subjective on our part. For this book, we picked either 100 or 120 candidates and those are the letters that appear in “World’s Greatest Direct Mail Sales Letters.” Some of them are older; there was man named John Yeck who has died since this book came from Yeck Brothers in Dayton, Ohio and some of the stuff that he had written was classic even to this time. I had stuff from Bill Jamey another old friend and another who died. These people are dropping like flies! He gave me what I regard as a superior piece of work.

Michael: I’m holding in my hand the “Greatest Direct Mail Sales Letters of All Time” by Richard Hodgson. Who is Richard Hodgson?

Herschell: Dick Hodgson was a fellow student with me at Northwestern. Dick got himself a job with the Franklin Mint in its early days of just becoming organized for a man named Joe Siegel, which is a legendary name in direct marketing. Joe Siegel in fact founded QVC, the sales network. They’ve gone through a number of hands since then, but Dick was his creative director and we’ve stayed in touch over the years. Dick wrote the book “Greatest Direct Mail Sales Letters of All Time.” He lives in Philadelphia, I’m told in retirement.

Michael: Was he a writer?

Michael: I’m looking here and you have multiple letters in this book.

Herschell: I thought there were two; there may be three or four. I don’t know how many are in there. You didn’t know that?

Michael: No, I didn’t know that.

Herschell: Well see, I’m glad I didn’t bring it up. That way it sounds better coming from you.

Michael: If you could pick one direct mail campaign that you are the most proud of and was the most exciting what would it be?

Herschell: That’s like asking which of your children you love best! The most successful campaign I ever had, and it’s dumb I’ll tell you in advance, was for a series of five Cinnabar collectors’ plates for Calhoun’s where we almost sold the whole thing out from the test mailing. It had to be the most successful plate mailing ever. I loved it because it was pure fiction, every word of that thing was pure fiction and it sold because we made up this folklore about a Chinese seer. It was “The Five Senses.” I didn’t want to call it the five senses; I called it “The Five Perceptions of Weo Cho” and Stanford Calvin to his eternal credit went along with the idea and Margot went to Taiwan to get these plates made of Cinnabar and we killed them with that campaign.

Michael: We talked about the real motivation about why people buy these plates.

Herschell: These were pretty by the way. There was more to these plates than just the collectible aspect. These looked good on the wall. I still have mine.

Michael: Do you think the stories, the pure fiction was what moved these plates?

Herschell: It’s all folklore.

Michael: That’s interesting. How many books have you published?

Michael: With all those books, do you have a writing deal with a publisher where you put out a certain amount of books every year or what?

Herschell: No, my principle publisher right now I would guess would have to be Amacon, American Management Association. They are an honorable and fast company. They published also what is now my favorite book called “On The Art of Writing Copy.” As you pointed out, here’s a book from MTC National Textbook, it’s out of print, and I hadn’t been told about it. My original publisher was Prentice Hall and they were bought by Gulf and Western and merged with Simon and Schuster. Everybody I knew there left and that’s why I went to Dartnell. Richard Hagel was my editor at Dartnell and he went to MTC and I went with him; that’s the evolution of this. Some of the more specialized books such as “Open Me Now” about envelopes or “How to Write Powerful Fund Raising Letters” were published by a specialty publisher in Chicago called Bonus Books. I don’t have a proprietary arrangement with any particular publisher.

Michael: Do you control all of the books you write? Let’s say you wanted to create a catalog of your own and sell them direct yourself, can you do that?

Herschell: I suppose, I’ve never had any desire to do that. That’s what publishers are for. I know a lot of people who publish their own books; well God bless them. I don’t see any reason to do that.

Michael: What would you say if you had a son who was sixteen and he said “Dad I want to get into writing”? What kind of advice would you give to somebody to have a successful career in writing?

Herschell: Writing to sell something, I would say saturate yourself in the marketplace. I think a man should start reading women’s magazines, women should start reading men’s magazines, and both of them should read children’s magazines and comic books. See as much of the world as they possibly can through everybody’s set of eyes, which prevents this proprietary “I am God” approach where you are hurling thunderbolts for Mount Olympus and nobody understands what you are talking about.

Michael: What do you think are the biggest mistakes made by people who start out in writing and want a successful career as a writer?

Herschell: I think it’s the arrogant assumption that “What I like is good for everybody.” I’m running out of time, Michael.

Michael: Okay, we’ll wrap it up. It’s been a pleasure, an honor and I think I’ve extracted some great information from you.

Herschell: I’ve enjoyed the conversation with you; it’s not really an interview, it’s a conversation.

Michael: It is a conversation, and that’s my style.

Herschell: On that level, if you have any questions that I haven’t answered email me and I’ll be glad to answer them.

Michael: I’ll get this recording up on my site in a hidden place and if you want to check it out and okay it with me. I would love to be able to share it with any of my listeners.

Herschell: You’ve got it.

Michael: Thank you very much.